Our veteran member Clive has written another great memoir of his youth -- this time with a trader in war scrap metal north of Rabaul in 1961.

Here's en extra from Clive's story- click "Read More" to enjoy the full drama and Clive's terrific prose.

Scrap metal and trevally heads - a lad’s tropical trading

by Clive Gartner- June 1, 2022

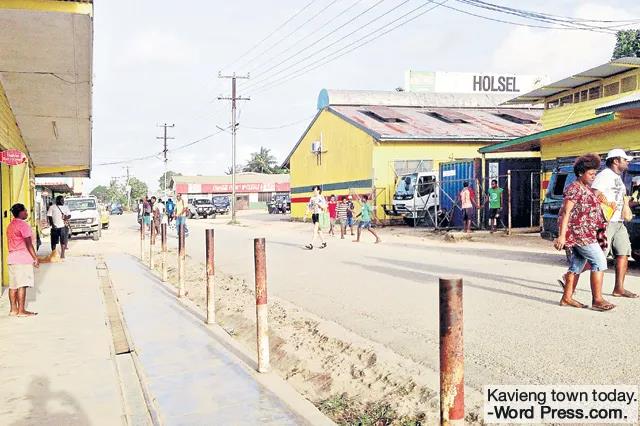

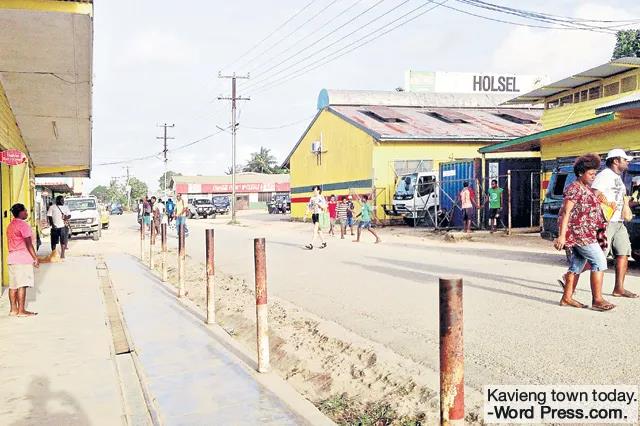

Early the next afternoon, as we approach the Kavieng pier, the crew run around the deck, ready to dock and unload the cargo. “The boys" man the deck and oversee the unloading. “Stay out of their way!” Darren says, and throwing on fresh shirts we head for the Pub.

It was a hot, humid PNG morning in January 1961 when I arrived in Rabaul, New Britain. I was fascinated by war stories, and I craved to learn more about near-home wartime events like the bombing of Darwin, the Kokoda Trail, and the Battle of the Coral Sea. This interest led me to PNG. My brother Murray and his family lived in Rabaul, and this gave me a great base to better understand the Pacific campaign.

It was a hot, humid PNG morning in January 1961 when I arrived in Rabaul, New Britain. I was fascinated by war stories, and I craved to learn more about near-home wartime events like the bombing of Darwin, the Kokoda Trail, and the Battle of the Coral Sea. This interest led me to PNG. My brother Murray and his family lived in Rabaul, and this gave me a great base to better understand the Pacific campaign. Murray managed an engineering workshop servicing quarrying equipment, trucks, tractors, boats and barges. Darren is one of his mates, the local auto wrecker and scrap metal merchant. We three met at the Friday after-work drinks at the New Guinea Club. The Club, a social mecca of the Australian Colonial administration overlooked Simpson Harbor and sat proudly on clipped lawns in the shade of two huge Morton Bay fig trees. The corrugated iron roof ran in one sloping descent from the hip of the roof to cover the wide verandahs surrounding the square building. This colonial architecture made the club a calm, cool and talkative environment.

It was 60 years ago, but my memory has retained faces, people, events, and buildings from the Australian Administration era, which Gough Whitlam ended on the 16th of September 1975.

I replay the scene at the club. Darren is six feet tall. From his spindly frame he looks like he's been on a long diet. His smoker's hack tells me he prefers cigarettes to food. Long straight sun-bleached hair falls to his shirt collar. His skin is wrinkled and dark, permanently cooked. A "rollee" sits comfortably between his lips. The cigarette smoke rises, and the slow turning ceiling fan moves it through the plantation shutters into the calm evening. The club atmosphere is conducive to conversation but the talk is too much about Murray and me; I want to know more about Darren. I figure he’s done more with his life than wrecking old cars for parts.

I listen eagerly and gather he’s forty. I wonder if he has military service and, if so, where? His physical appearance ages him more, and his exposure to the tropics of New Guinea has obviously been more than a year or two in Rabaul.

To keep the conversation lively, I buy another round and ask,

"How long have you been in PNG?"

He launches into a long explanation; I sip my SP lager.

“All my life in PNG. I was born in Rabaul in 1925. My father was a plantation manager on a copra plantation at Kokopo, about twelve miles down the coast from Rabaul. Mum ran our homeschool, but the native village was the second home for us four kids. I could beat anyone shimming up a coconut palm. We kids talked Pidgin outside home, and when Mum sent us to high school in Brisbane, she feared we might not cope. But we all got our certificates. They sent little me, the youngest, off to a Trade school.

When I was 14, the Yanks entered the war after Pearl Harbor and the action soon moved southwards towards Australia. The newspaper reports on the Battle of the Coral Sea, which saved Australia from Jap invasion, were better reading for me than a Phantom comic.

I counted down the days when I could sign up at the Army recruiting depot. Whithin days of turning eighteen I was off to the Atherton Tablelands for jungle warfare training. For six weeks, it was full on 24/7, slithering through mud, crashing through obstacle courses and firing Owen guns from the hip, on the run, at life-size targets of Japs hidden in the bush. The instructors were merciless. Their call "get fit, get smart, get a Jap" r ang in our ears from dawn to nightfall. But I got sent instead to Darwin to guard the telegraph station and patrol the swamps looking for imaginary Jap infiltrators. What a letdown. Boy, was I glad to get drafted to the 8th Battalion and on to Lae for the real stuff -- that was August 1944.”

ang in our ears from dawn to nightfall. But I got sent instead to Darwin to guard the telegraph station and patrol the swamps looking for imaginary Jap infiltrators. What a letdown. Boy, was I glad to get drafted to the 8th Battalion and on to Lae for the real stuff -- that was August 1944.”

ang in our ears from dawn to nightfall. But I got sent instead to Darwin to guard the telegraph station and patrol the swamps looking for imaginary Jap infiltrators. What a letdown. Boy, was I glad to get drafted to the 8th Battalion and on to Lae for the real stuff -- that was August 1944.”

ang in our ears from dawn to nightfall. But I got sent instead to Darwin to guard the telegraph station and patrol the swamps looking for imaginary Jap infiltrators. What a letdown. Boy, was I glad to get drafted to the 8th Battalion and on to Lae for the real stuff -- that was August 1944.”I’m spellbound “Wow, what an experience for an eighteen-year-old. You were too late the Kokoda Track and the Owen Stanleys; did you see action against the Japs when you got to Lae?”

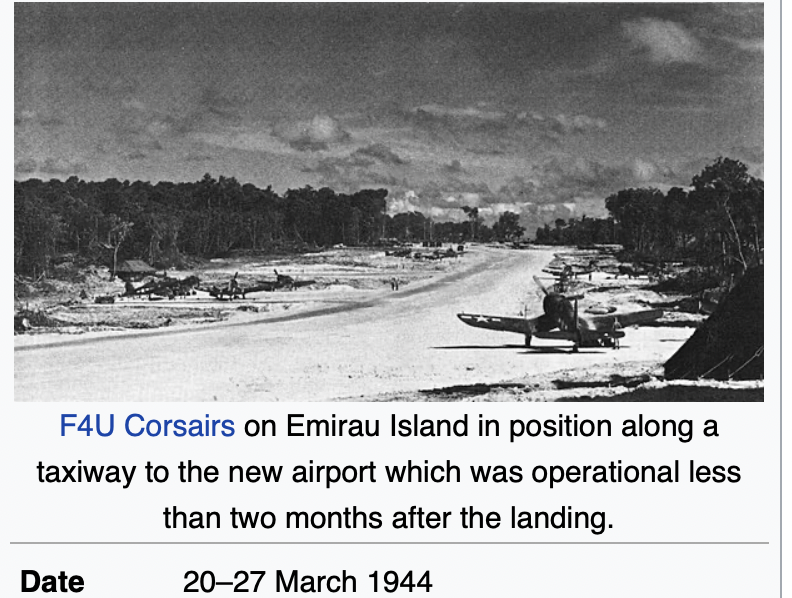

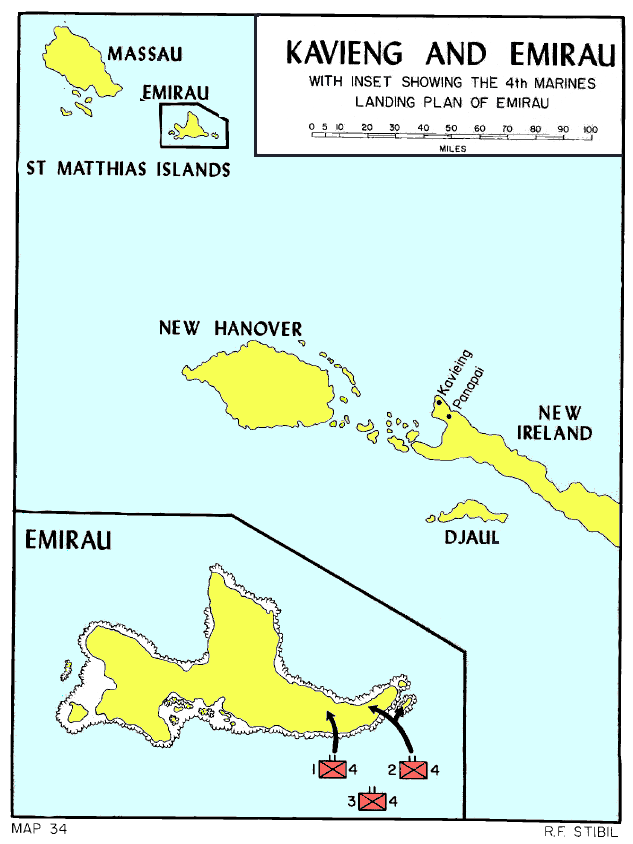

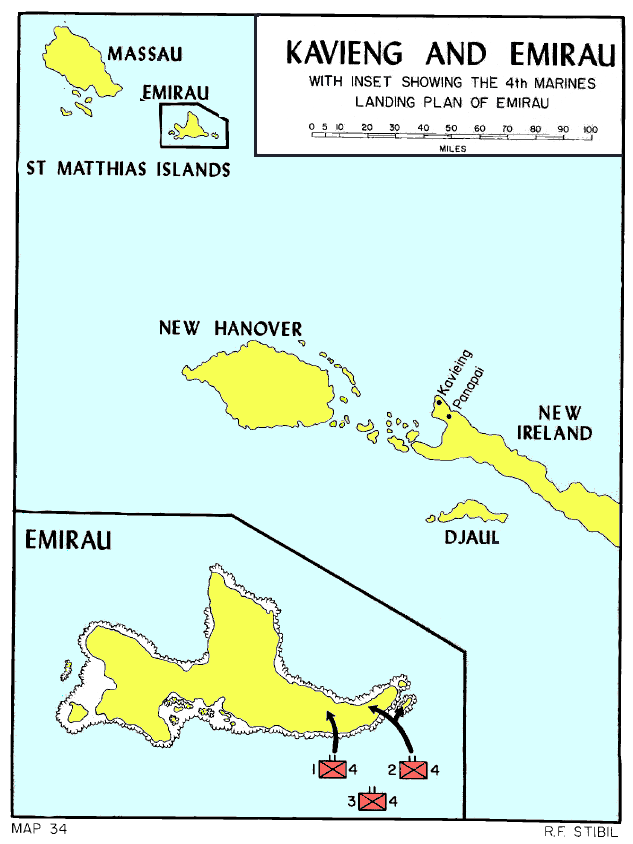

“No, we were too late. We ended up on Emirau, an island in the Saint Matthias Group about ninety miles north of Kavieng. In 1945, the 8th was sent to mop up the Japs in the outer islands and finally to Bougainville to finish off the last of them. In May 1946, my Army days ended when the 8th disbanded in Brisbane. Rabaul was closed to civilians until 1949, and as soon as the door opened, I was in, and I’ve been here ever since.”

Had you been on Emirau in pre-war days?

“Yes, a couple of times. Dad had access to the plantation work boat and the family would go there regularly for a few days fishing and snorkeling over the coral reef. Enjoying our holiday in the island’s pristine beauty, we couldn’t imagine that the US Marines in 1944 would land over 20,000 men on the island. Emirau was the final link of Operation Cartwheel, MacArthur’s strategy for encircling the 110,000 Japs stationed in Rabaul. Isolated by the Allies' seaborne blockade, these troops sat out the war, trapped. After the surrender in August 1945, the Allies took over two years to repatriate these captured troops to Japan. The bastards were all fit and healthy on returning to Japan, unlike the emaciated Australian POWs returning home from Japanese captivity."

"Did your parents stay in Rabaul during the war?"

"Mum was lucky. She evacuated late in '41, just before the Japanese bombing and occupation. Dad stayed on and joined the Coastwatchers. They hid along the coast and were supported by locals and supplied by Allied airdrops and PT boats. They radioed Allied command on Japanese shipping and planes. For secrecy, the radios transmitted on a rarely used frequency, but the Japs knew how to locate them. A patrol ambushed Dad as he sat at his Morse keypad. He was one of the six planter recruits rounded up in New Britain and shot by them in 1944."

To cover some emotion Darren looks down at his Havelock tobacco pouch and rolls a smoke. I feel he does not want the conversation about his father's death to continue. I edge back with another round and ask,

"Is there still war scrap to be picked up on the outer islands?”

" My oath! What’s left is scavenged out of the bush by the locals. We go on regular buying trips and bring the scrap back to my yard here in Rabaul. Want to join us on our next trip?”

“Do I! When?”

“Dawn tomorrow for a week."

My brother Murray grins: "Go for it. You know your way around a boat, and there’s no better island-hopping skipper than Darren. It'll blow your mind".

I find the Niad at the pier, a fifty-ton island trader; three muscular Trobriand Islanders are the crew. They wear no shoes, no hats, only tattered shorts. Their shining black skin glistens like polished ebony in the early morning sun. I get smiles and welcome in Pidgin. I don’t need to understand the language to know we'll get along as shipmates.

Darren greets me for a boat tour.

"You can bunk down below in the cabin. There’s a bunk opposite the galley, and I'm topside in the wheelhouse. My bunk runs amidships behind the wheel and engine controls; I'm ready for action 24/7 — the crew bunk in the foc'sle behind the chain locker. You won't see them much at night. They head for their hammocks once they’ve scoffed the evening grub. They are comfortable up forward.

“I hope you'll like island food. We eat fish, fish, and more fish, yams and lots of coconut cream squeezed from fresh coconut. If the diet gets monotonous, you might find the odd can of Spam or baked beans in the galley for a gourmet snack. We're good for coffee, but there's no beer on my working ship."

A six-cylinder Perkins diesel squats on its mounts in the engine room. This engine has been serviced by my brother and I’m confident it will return me safely.

A small crane swings crates of trade goods on board. The hold fills with general merchandise to re-stock island "sari-sari" stores—cartons of canned meats, soft drinks, cigarettes, lollies, and bags of rice. In the wheelhouse, I view the navigation chart with Darren. First, Kavieng, New Ireland, one hundred miles out, then the Saint Matthias Island group, and we finish the leg on Manus then direct home for Friday night drinks at the Club.

Darren hits the engine start button; the Perkins rumbles and we chug our way through Simpson Harbor. He detours to show me a submerged shot-down B-25 Mitchell bomber. Its US Air Force star is still visible on the wings. The Perspex cockpit canopy is missing, but the metal frames of the flight crew seats are there, and the instrument panel and the flight control levers, all encrusted in a light layer of coral.

I ask Darren, “Did the crew survive?”

"Most likely, the fuselage isn’t severely damaged. The Japs would have picked them up and taken them to their hospital in the tunnels. Who knows what happened from there? During occupation, their engineers bored over four miles of tunnels into the volcanic rock surrounding the harbor. They built hospitals, engineering workshops, accommodation, and military headquarters in the tunnels, all safe from Allied bombing”

Darren points to the still visible tunnel openings. Our engine thumps and we move out of Simpson harbor into the Bismarck Sea, next stop Kavieng. It’s a perfect day to start this leg, light breeze, flat seas. Darren sets the autopilot on the course, 30 degrees West of North and we move effortlessly through the turquoise waters on the overnight leg. The sunset puts on a big show, the golden ball of the sun disappearing slowly below the horizon and leaving a gentle glow in the low- set cumulus clouds.

Darren points to the still visible tunnel openings. Our engine thumps and we move out of Simpson harbor into the Bismarck Sea, next stop Kavieng. It’s a perfect day to start this leg, light breeze, flat seas. Darren sets the autopilot on the course, 30 degrees West of North and we move effortlessly through the turquoise waters on the overnight leg. The sunset puts on a big show, the golden ball of the sun disappearing slowly below the horizon and leaving a gentle glow in the low- set cumulus clouds. Early the next afternoon, as we approach the Kavieng pier, the crew run around the deck, ready to dock and unload the cargo. “The boys" man the deck and oversee the cargo. “Stay out of their way” Darren says, and throwing on fresh shirts we head for the Pub.

After more than a few beers, we cast off and headed for Emirau 95 miles northwest. Thankfully, water police and breathalyzers don’t exist in the 60’s PNG. Once we clear the harbor Darren sets the autopilot heading for Emirau and announces it’s his nap time. “Don’t worry about a thing, the crew know the drill” and with this, one of the crew moves without question into the wheelhouse and takes over first mate duties. Whitin minutes Darren’s snoring confirms the boat depends now on me and the crew.

With a couple of hours of daylight, left the fish should be ravenous. One of the boys grabs the binoculars from the wheelhouse, scans ahead and excitedly point to cormorants circling, diving, and hitting the water in an explosion of spray. My fishing friends jump up and down screaming “Skipjack, skipjack!” and soon we’re in a school. The first mate reduces speed and lines go over the stern. The fishing frenzy begins. We are over a reef seething with trevally and the boys are soon hauling in eight-pounders. They use basic rods with bright orange lures attached, and I can’t believe their strength and dexterity. As the skipjacks hit the deck the boys gut them and place them between layers of ice in the large, insulated fish box. The deck is awash with blood and fish entrails, cormorants circle the boat, screeching, screeching, then dive into the sea to retrieve fish guts washed overboard. The crew squelch through the fish entrails in their bare feet, bits of fish innards squeezing between their toes. Laughing they point to my still white Dunlop Volleys, indicating I should get them off. Their mirth is infectious, and I join in the fun but keep my shoes on. The catch will be used to compensate Islanders who load our war scrap.

A beauty, a ten-pounder trevally, remains in the scuppers -- its shiny blueish silver body with forked tail flapping, bang, bang on the deck. The boys prepare it for dinner. I look down at the gory fish cleaning spot, blood and fish entrails litter the deck and the head of our dinner fish looks up at me. The high sloping forehead sports a large eye staring at me. I shudder and feeling a little squeamish kick the head over the stern. My fishing pals scream native profanities:. I quickly get the message: kicking fish heads overboard isn’t appreciated. Darren bleary eyed from his nap emerges and calms down the drama.

“Clive old mate! Fish head is the key ingredient in Trobriand Island soup and the eyes are the delicacy. The boys had soup on the menu for tonight with that prized head. Don’t worry, the fish slowly basted on the BBQ will be so good we wo n’t miss the soup.”

n’t miss the soup.”

n’t miss the soup.”

n’t miss the soup.”I apologize to the crew as best I can for my lack of culinary understanding and soon smiles replace the anger. No soup tonight but the fish is delicious, stuffed with native herbs and smothered in freshly squeezed coconut milk.

We motor at eight knots throughout the night, make Emirau Island at daybreak and anchor off the beach. Locals line the foreshore, the scavenged war scrap from the bush in heaps ready to trade. The crew launch the tender and we head for the beach. Darren wears a leather bookies’ bag labelled “Darren” in large white print. The bag is heavy with one-shilling coins, wads of one-pound notes and a small cache of fivers. We also carry the ice box full of fish, together with a large scale for weighing and a stack of hessian sugar bags branded Sugar, CSR Australia, 56 pounds. Darren is ready to haggle.

He hangs the scale under the eve of the "sari-sari” store. The fun begins, locals crowding around me, their lips stained with beetle nut juice and keen to get their bag hooked on our wobbly scale. I hoist each bag, there’s lots of laughter. Darren has a standard call in rapid pidgin, “pulap pulap bilong mi, wanpela quidi” (full up, full up, one quid) and sugar bags fill with brass shell casings, lead battery plates, copper wire and tubing and bits of aluminum hacked off abandoned aircraft engine blocks. The frenzy continues throughout the day. The scale always read 20lb which earn the seller a quid. If a seller disputes the weight it’s settled with a laugh and extra one shilling coins. A bob here or there makes everyone happy. This jovial trading goes on all day. The tender runs back and forth to load the scrap. We finally pack the scale and left-over sugar bags into the empty ice box and close shop. As the sky darkens and villagers ashore light kerosene lamps, we motor off to repeat this procedure daily at nearby islands.

Our last stop wis Manus. The trading here is pricier and more sophisticated. Sellers demand more money and Darren hands out more fivers. A hard day’s trading finally ends and with the hold full of scrap and Darren’s bookie bag empty, we set course back to Rabaul.

One week has passed and we are back at the New Guinea Club for Friday night drinks. I relate to Murray the trip highlights and Darren interrupts,

“The boys wanted to string Clive up on the radio mast, he kicked a fish head overboard.. They were upset but soon cooled down when I pointed out his once white Volleys were now well splattered with fish blood. He’d been christened to be part of the crew”.

Darren rolls yet another smoke as I reflect on his island trader skills and accommodating personally. He’s opened my eyes to the real war in the Pacific, a different version to that reported in the Courier Mail of my teenage years. The Japanese bombing flattened Darwin, only a handful of the original buildings were standing when Darren arrived in 1944. I had no idea the Japs dropped more bombs on Darwin than they dropped on Pearl Harbour, killing nearly 300 people. But now it’s time to return to the boredom of work life in industrial Melbourne.

I will not forget, ever, my trip on the Niad when I got serious about war scrap… where relics of deadly combat were transformed into smart wealth for my scrap-business mate and great pocket money for hundreds of delighted islanders. #